Time for some good pension news and bad pension news. The bad pension news is that the Austin Police Pension’s funding level quietly sank from an 88% funding ratio to just 58% over the last two decades. The 58% funding level news came at a pension board meeting today, which will be summarized at the end of this article.

A 58% funding ratio means there is only 58 cents in the pension fund to pay for every dollar of retiree benefit liability.

The good pension news is that Texas law limits how far a pension can sink before the state steps in to force reforms. The APD officers’ pension has drifted right into the state’s crosshairs, so after decades of downward drift, some proactive change should finally (hopefully) coming.

On July 17th, the Austin Police Retirement System’s board of trustees met to hear from its newly-selected actuary, Gabriel, Roeder & Smith (GRS).

Before discussing the GRS bombshell, this article will briefly explore the following:

- History of the pension since the 1990’s

- Key problems and moral hazards that face the pension

- What recent actuarial assumption changes mean

- What the 2018 actuarial valuation presentation said

Short History of the Austin Police Pension

1990’s

Between the early 1990’s and 2015, the Austin police pension increased both its payout to retirees as well as the contribution rate from members and the city (see page 73 of the 2002 Annual Report).

In 1993, the Austin Police pension system paid a smaller 2.3 multiplier to retirees. Members paid 9% of payroll and the city contributed 12%.

In 1994, the city raised its contribution rate to 14%. It continued raising to 16% in 1995, and then to 18% in 1996. Member contributions remained at 9%. At the same time, the multiplier was raised to 2.8 in 1995 and then to 2.88 in 1997.

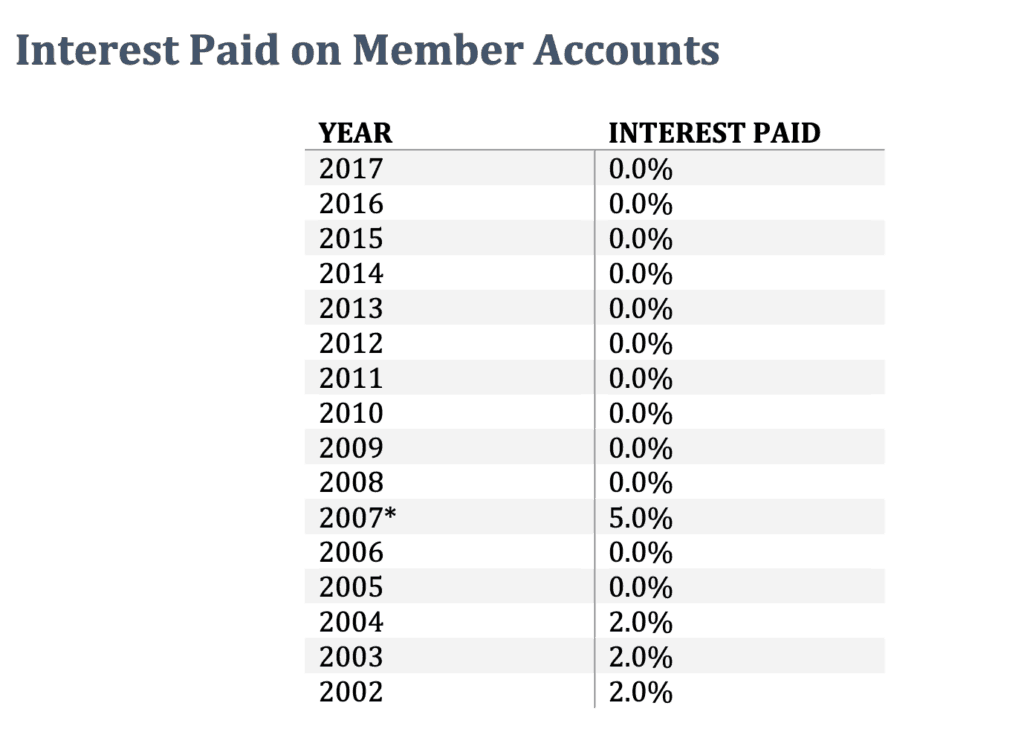

Throughout the 1990’s cost of living (COLA) adjustments were given to retirees at roughly the rate of inflation. These COLAs ranged from 2-4% per year. A 5% interest rate was paid on members’ contributions for those who left the system early.

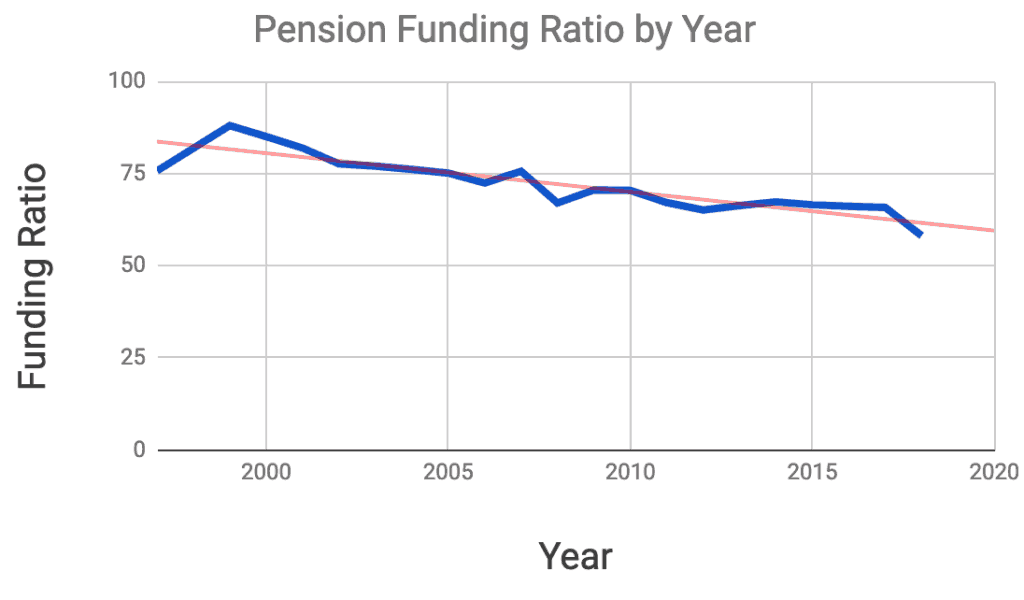

In 1995, the pension board raised the multiplier to 2.8, and then to 2.88 in 1997. Contribution rates remained at 9% for members and 18% from the city.Starting in 1997, the pension funding ratio stood at 75.7%. After a market runup, the pension funding ratio peaked at 88% funding in 1999.

2000’s

At the start of the new millennium, the pension board raised the multiplier again to 3 (see page 92 of the 2011 Annual Report). But a year later, the 2001 biennial report showed the funding ratio had dropped down to 81.9%. It fell again to 77.6% a year later. As the ratio sank to 75% in 2005, something had to give to stop the bleeding.

In 2005, both COLAs paid to retirees and the interest paid on members’ deposits were reduced to zero. A 1% COLA was paid in 2007, but since then both the COLA and interest paid on members’ contributions remained at zero.

By 2006, the funding ratio fell to 72%. Member contributions were raised to 11% In 2007, the multiplier was raised to 3.2 and member contributions climbed to 13%.

2010’s

Following a 26% loss of asset value in 2008, the city began raising its contributions (see page 103 in the 2017 Annual Report). The contributions climed from 18% in 2008 to 18.63% in 2009, 19.63 % in 2010, 20.63% in 2011, 21.63% in 2012, and leveled off at 21.313% in 2015.

Despite a record decade-long bull market plus the increased contribution rates, the funding ratio fell from 70.4 in 2010 to the last released valuation of 65.8% in 2017. As of this writing, July of 2019, the 2018 report has not yet been posted on the ausprs.org website, but at today’s meeting the actuaries pegged the December, 2018 funding ratio at 58.1%.

What Problems Face the Pension?

Moral hazard

One way to summarize the inherent problems facing any pension is through the lens of moral hazard. In pension terms, moral hazard can be summarized as people in the present day desiring benefits but wanting the cost and problems of paying those benefit to go to future generations. This puts taxpayers, politicians, active employees, and retirees in competition over who foots the bills for benefits.

Here’s how that goes – Taxpayers want a fully-staffed police department to suppress crime and disorder. The politicians they elect recruit officers by offering attractive benefits, like a decent pension with a competitive multiplier. People accept the offer, sideline their private sector careers, and go to work for the police department. Everyone is happy.

Here’s where the issue starts – Over time, when adverse events occur, like the depression of 2008, pensions are sometimes set in a downward spiral. As the funding ratio drops, moral hazards become more visible.

Politicians have their own projects they’d rather fund than a boring old pension obligations, like parks and trains. Members don’t want any more of their paychecks to go into the pension. Taxpayers don’t want to pay more tax dollars to fund a pension for other people that they themselves don’t have. Pension board members may not want the drama that comes with sounding the alarm of a a pension on a downward funding slide or asking politicians for increased funding.

The end result, like what has occurred in countless other pensions, is that the can gets kicked down the road and the problem festers. How has this played out?

Underfunding

Underfunding occurs when a pension pays out more money than it brings in through contributions and earnings on investment. This could be because people are living longer than expected, investment returns don’t meet expectations, or a myriad of other actuarial assumptions that don’t come to fruition.

As the red trend line in the graph above shows, underfunding and a declining funding ratio have been occurring for a long time. Without intervention, this decline will accelerate as fewer and fewer assets are available inside the pension to generate revenue to keep up with benefit obligations.

No COLA

Cost of living adjustments (COLAs) are a common feature of pensions and annuities. Currency inflation reduces purchasing power, so pension plans (social security being a good example) routinely increase the annual benefits through cost of living adjustments so that retirees can maintain a stable purchasing power.

No pension I am aware of advertises a zero-percent annual COLA as a permanent feature. Without a COLA, the value of the dollars paid to retirees falls, and their standard of living erodes.

No interest paid on member deposits

Officers give mandatory paycheck contributions into the pension. If they leave before becoming vested (at ten years) or choose to receive their contributions back if they leave before full retirement, they receive back the exact dollar figure they paid into the system from their paychecks.

OK, but what about interest earned on those dollars? Policing is rough on people, and many are going to leave before reaching full retirement. You would think that, as a matter of fairness, some percentage of interest earned on those dollars held in the pension would be paid to the members upon their departure. After all, the members’ dollars were productively invested and earning money inside the pension.

Because the pension was underfunded, paying no money on members’ deposits was a way to slow the decline in the pensions’ funding level. Without interest paid on deposits and inflation eroding the value of old dollars, the money reimbursed to members is worth less than what they paid in. The difference in value between what they receive and what those dollars earned in the pension remains with the people who stay for full retirement.

What do Recent Assumption Changes Mean?

In May of this year, the pension board of trustees adopted new actuarial assumptions following an experience study done by GRS. What do these assumption changes mean? Here are two of the more prominent changes:

Reduced investment return assumption from 7.7% to 7.25%

“Among the 129 plans measured, 42, or more than 30 percent, have reduced their assumed rate of return since February 2018, and more than 90 percent have done so since fiscal year 2010, resulting in a decline in the average return assumption from 7.91 percent to 7.27 percent.”

National Association of State Retirment Administrators

The higher the expected rate of return on pension assets, the more money the assets generate to pay out benefits. This reduces the amount of money the actuary says the city and members need to contribute.

The drawback is that high expected rates of return increases the risk that (1) the investment returns will fall short and (2) that reduced contribution rates will exacerbate funding shortfalls.

Reducing the excepted rate of return reduces the risk of underfunding and is in line with national trends in changes to pension assumptions.

Updated Mortality Assumptions to Reflect Longer Life Spans

The focus on police wellness is a much-needed and welcome development. From a pension perspective, increasing the lifespan of retirees puts additional strain on the pension. If people live longer than the pension expects, underfunding will result if contributions are not raised or other benefits are not reduced.

Old mortality tables reflected the notion that officers would die shortly after retiring. This meme may have been the case decades ago, but it is not accurate today. By adopting new mortality tables that reflect longer life spans of retirees, the pension can get updated data to use in calculations determining what level of contributions or asset rates of return are needed.

What Did the 2018 Actuarial Presentation Discuss?

On July 17th, the board kicked off its meeting with the much-anticipated, yet pin drop-silent and sobering, presentation of the 2018 experience study. Representatives from GRS Retirement Consulting explained the process of how an experience study works, and then got down to numbers.

GRS pointed out that the pension, according to their calculations, is only 58.1% funded with an unfunded actuarial accrued liability of $582 million dollars. The present value of pension assets, as of December 2018, was $808 million.

GRS representatives pointed out that the pension, “is no longer projected to become fully funded over any time period based on current contributions and assumptions. To put the pension on a path of fully funding the pension in 20 years, the city would need to raise its contributions by sixteen percent from 21% to 37.3% of payroll.”

For a 30 years-to-fully-funded time period, the city needs to increase the payroll contribution by about eleven percent from 21% of pay to 31.9% of pay .

“Without any change to contribution rates, pension assets are expected to deplete within the next 50 years,” the representatives concluded.

To put that into perspective, the City of Houston (following its underfunded police pension fix) currently contributes 32% of payroll. The City of Dallas now contributes 34.5% of payroll to its underfunded police pension.

Next Steps

After the presentation, pension board members pointed out that they are not discussing any benefit changes or imposing any benefit changes. The board said that they will work with active members, retirees, and the city to come up with solutions to fund the pension.

The board and the executive director said that they would host informational sessions in the next several weeks to inform members and retirees about the status of the pension.

Thanks for the rather sobering update. How will an anticipated upsurge in expected retirements combined with reduced staffing expectations impact possible future contributions ?

In January, contributions from both members and the City will increase significantly, so the funding level of the pension should begin climbing out of the hole it’s in, even with the current upside-down staffing trend.

They should strive to move the transient EMS workforce from COAERS to the APD retirement to bolster their funding levels.

I feel bad for the EMS folks when it comes to retirement funds. Almost nobody who works as a medic stays a medic long enough to receive COAERS benefits. EMS would be better off in a retirement program that fairly rewards people who work shorter times on the job, like a 401k or a defined contribution pension plan with a very short besting period.

Same stuff different day! Nothing is helping us retirees who are struggling to make ends meet. Please get the City to contribute more to our system make it solid as a rock. If I could get just a 1% COLA increase every year I would be happy.

Even 1% is not much but it is better than nothing at all!!!